The people and places that made Bungonia what it is today

Hazel Ayre: Memories of Bungonia

As recorded on a cassette recording

Hazel Ayre

Hazel AyreI often wish that there had been stories written of the young lads teaching in half-time schools around New South Wales. They had rough lives and lonely lives.

They were called pupil teachers. Though what else they could be expected to teach is rather a mystery.

My dad was one of these. When I was young and lived in Bungonia, each weekend some of these young teachers would come to the schoolhouse looking for company and someone to talk to. I thought they were a nuisance as I wanted my dad to myself. My dad spent 43 years teaching in country schools. He was a good teacher.

Looking for Bungonia Specific History Archives? They are held in Goulburn Workspace by courtesy of Goulburn Mulwaree Council. Please use our contact form to arrange supervised access. You cannot do it through the council or the library.

Dad was born in Majors Creek and came with his family to Goulburn where he went to to primary school. In those days, Majors Creek had a population of many thousands as they had discovered gold there. My mother’s wedding ring was made of Majors Creek Gold.

Dad’s father was a mason and help to build the Goulburn Base Hospital. Dad was Dux of South Goulburn School and for many years had his prize book, about the districts of central Africa.

After he left primary school dad decided that he had had enough of school and asked his dad if he could go out to work with him. He lasted one day before discovering that such hard physical work was not his cup of tea.

At the age of 17 or 18 he went to the Queanbeyan district and taught at two or three half-time schools in the district. One of the places he remembered most was living with an Irish family in the Tinderry mountains. The family consisted of a melancholy mad Irish woman, her two sons, a small daughter and a husband who was away most of the time working in the bush.

My father would tell the story of how she would sit in her rocking chair saying worra, worra, worra, and dad would sing Irish songs to cheer her up. Not far from the Tinderry mountains was the little settlement of Urila where the Naylor family lived and where he met my mother, Katherine Mary Edith Naylor. She was only 18 when they married.

Early in their married life they came to the little village of Kingsdale outside of Goulburn. While they were there, Roy, Daisy and Olive were born.

One day, in Goulburn, at the supermarket, I met an old man in his 90s who didn’t know who I was but told me that his teacher was the most wonderful man he ever knew.

He said he was a boy who lived on a farm, sometimes so tired that he would fall asleep in the playground and this kind teacher would pick him up and carry him when he was tired.

He said he was given a wonderful education and the teacher did not even use the cane. He said he went to school at Kingsdale and of course, I found out his teacher was my dad. When I told him who I was he was so excited he hung onto me.

The influence of a good teacher goes on for many generations.

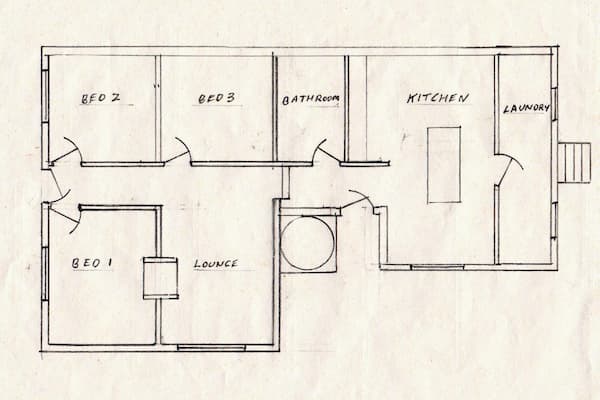

The Bungonia Schoolhouse, drawn from memory by Bernie Ayre

The Bungonia Schoolhouse, drawn from memory by Bernie Ayre

There were five kids in the family. My father was a wonderful father, funny and loving. He had a good baritone voice and used to come into Goulburn to sing with the local musical groups.

About the turn-of-the-century, he moved to the one teacher school at Bungonia where he was to stay for the rest of his teaching career. In the early days it was rather a large one teacher school.

Dad was a staunch Church of England member, and was the Rector’s warden for most of the time he was in Bungonia. At a time when sectarian intolerance was rife, dad managed to make good friends with the local Roman Catholic people in the village, especially the postmistress.

He would often entertain both Church of England ministers and sometimes the priest who came to the village church.

There were two boys in our family, Roy, who came home wounded from the First World War, and Jack, who died in Thailand in 1944. Both the boys were excellent sportsmen. They played cricket and tennis and Jack certainly went to country week for cricket. In the Goulburn Evening Post in the 1920s there are many articles about his sporting prowess.

Roy played tennis most of his life.My father was well known in Goulburn and many of the splendid concerts we had at Bungonia featured artists from Goulburn.

There was plenty to do in the village, especially at weekends. We had concerts, fates, harvest festivals, picnics and dances. Sometimes the entertainments were held in our village, sometimes we travelled by a horse and buggy to surrounding villages.

Dad was very keen on all sports except the rifle club. He believed in active sports, but at weekends the farmers came up to the local rifle range, lay on their stomachs and fired their rifles at targets.

At weekends we would go for walks, often to places where there had been houses in the past. Many of them, although only in ruins, had fruit trees still growing near them and we would pick the fruit in season and bring it home.

I am one of the few people who know where the old courthouse was in Bungonia. In my youth you could see the ruins of it, and the whipping post where the convicts were whipped. We even found some manacles in the grass.

Miss Styles, who lived in the parsonage across the creek, told the story of how when she was a little girl the family coming into church from Reevesdale would pass a line of convicts going home back to Reevesdale, with their backs bloodied from a beating. The magistrate would come out from Goulburn on a Saturday and they would receive their lashes on a Sunday.

I remember dad talking to an old lady about bushrangers. In her opinion, they were not the glamorous outlaws as depicted in some books and movies. The settlers knew them for what they were. It was the troopers who were the heroes. We should remember them.

The old lady remembers giving food and tea to either Gilbert or Ben Hall, somewhere near Young or Yass. The great gallantry of the bushrangers did not fool them at all. They were not afraid of being attacked by them, because they knew that these desperadoes did not want to make any more enemies. If they had molested any of the women, who were scarce commodities, they would have been ruthlessly hunted down.

Daisy, Katy, & Hazel Ayre

Daisy, Katy, & Hazel Ayre

In my childhood, the native aboriginal people had long gone, but there were a few traces of them left near the village. I remember a clearing in the thick bush that had two huge trees on either side of the clearing, decorated with deep cuts. I think it was a corroboree ground.

It was the way of things in those days, when they began to clear the land, they cut those trees down and burnt them. As a child we often found axes and sharpening stones which we brought to school. In the schoolroom there was a big glass case for these interesting things, as well as minerals and other stones. Some time, probably in the 1960s, they all disappeared.

There is a story, I don’t know whether it is true or not, that an old aboriginal would come up from the gullies with gold. The blacks only came up to the Monaro in the summertime. The rest of the year they spent on the coast. Our local aborigines were wiped out in the last century, long before the American Indians were cleared from their hunting grounds.

Although I am 87 years old as I write this, I have never spoken to a native aboriginal.

Yet I love this country like they did. I feel the companionship, alone in the bush.

I feel part of the country. My heart is still in the hills and the bush to this day.

At the weekend, our little village was a hub of activity. Outside the post office and the local hotel were buggies, sulkies and horses tied up. There was tennis at the local tennis court and cricket. In the village there were at least three places where cricket had been played in the past. It was a very social occasion. There were marvellous tennis tournaments. The ladies also played and we had many splendid tennis players.

One of the other highlights of the year was a school picnic, which was held on the flats, down by the creek where the old pine trees used to be. It wasn’t just our school, but schools including half-time schools round about came and joined with others on the day of the school picnics.

There were lots of races, including egg and spoon races, three legged races, sack races and of course running races. We always had a lolly scatter and everyone seemed to win some prize.

There were also harvest festivals in aid of the local Church of England, and lots of people from the district came to the festival which was held in the hall. There was a half holiday for Empire day, which was a time for a bonfire, crackers and lots of fun. I think the biggest cracker I ever let off by myself was a tom thumb.

September the first in our part of the world was Wattle Day. It wasn’t a holiday of course, but we went on what was supposed to be botanical walks. While the girls may have walked sedately, the boys would often make swords from the grass sticks that grew everywhere, and generally had a good time. We always had a wattle Queen.

Polling days did not come around all that often, but they were held at the school and it was a great reunion day. The church ladies always had afternoon tea on the veranda of the school house and I often hid behind the curtains in my bedroom and listened to their conversation.

Unfortunately, I had no one to hand on the gossip to. My mother was very much against gossip, and my father, who was the confidante of most of the farmers in the neighbourhood, writing their letters, helping with their tax et cetera, was a soul of discretion. It was one of the fears of people who could not manage their own business because of literacy problems, that other people would learn from my dad information that was confidential. They need not have worried.

One of the things that we were taught as children, and which has stayed with me all my life, is that we were forbidden to call older people by their Christian names. I am still startled today when people call me by my Christian name.

Funerals also were startling events in our small community. Fortunately they did not happen very often, but for a really big funeral I can still remember standing and watching two black horses complete with black plumes and men in tall black hats and the mourning carriage going down the road that led to the cemetery. It was another time for social get-togethers.

One other special occasion I can remember were the farewells and welcome home for those who went to the war. There was bunting, socials and dinners and gifts. I remember one fellow saying it was an honour to have fought and bled and died for his country.

One of the impressions that I still have of the First World War is as a child, seeing the posters that were put on trees and fences and telephone posts, usually painted red with graphic propaganda, or a picture of a man with his finger pointing at me.

We saw our big brother and many friends go to the war. In those days of course, there was no radio that could tell you very much, so dad would wait for the paper to read the headlines and look at the casualty lists. Roy went at 17 and dad and Mum signed the papers. (Gretel checked up on this and found that he enlisted a day or so after his 18th birthday and he got someone else to sign his parent’s names.)

Roy was a very gentle man and his experiences in the war were to affect him all his life. He was slightly wounded and gassed and when he came home he did not speak about his experiences, except sometimes to me. This happened to many men who came back home. In those days there was no such thing as counsellors and men kept these things to themselves. I think the trauma of the Flanders Fields helped to shorten his life.

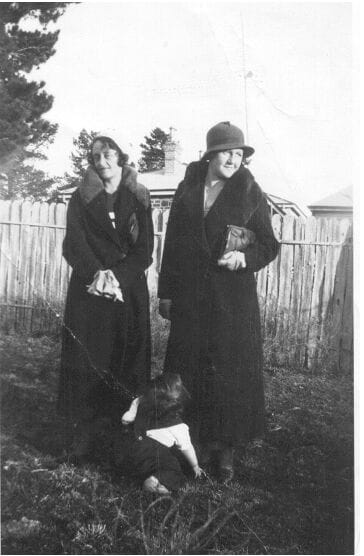

Olive Lee, Hazel Ayre & Gretel Ayre circa 1934

Olive Lee, Hazel Ayre & Gretel Ayre circa 1934My two sisters, both of whom were older than me, giggled their way through school and married and went to Sydney. My little brother Jack was four years younger than me. We were good mates. Jack had a good education at high school and had a good job in Sydney until the Depression came. He was shunted off to war in 1940 and died on the infamous Burma Thailand Railway in 1944, aged 32.

When one is a very small child, one tends to live their life close to the ground. I remember the chickens, the lambs and all the flowers that grew wild. In spring there were so many beautiful tiny Australian flowers. Daisies, yam flowers, chocolate flowers, bachelor’s buttons, just to name a few. We ate quite a few growing things. It’s a wonder we did not kill ourselves.

We ate the flat white groundberries. We carefully lifted the groundberries and made sure we did not pull them away from the soil. We ate manna from the gum trees, wild cherries which were very sweet and had the seed on the outside. They came from further down the gullies.

We ate wattle gum and wild mushrooms and hawthorne and briarberry pulp and monkey nuts, now called pinenuts and sold in health food shops.

We were told never to eat the seeds of the briarberries or we would die. We were also warned about the monkey nuts and were told by other children that they would grow pine trees in our bellies if we ate them.

We also had a wonderful creek that flowed through the village. We had some close shaves that we never told our parents about. The special time was when the creek flooded. There are few floods in the creek now, partly because it is choked with reeds. We knew every tributary and loved playing in the caves and cubbies we made in the eroded creek walls. We loved to find hollows of fuzzy grass and jump in them, not caring that there may be pointed sticks or snakes. We had a healthy respect for snakes and bulldog ants.

We loved to see the floods coming down, raced down to the bridge to watch the tree trunks come down and some of the farmers fences. Then we explored all the new waterholes and all the new pieces of quicksand. You could sink up to your waist sometimes in the quicksand.

On moonlight nights we walked to the deep water holes in the creek where dad caught eels and brought them home for Mum to cook. We skinned them and Mum cut them into slices, rolled them in egg and breadcrumbs and fried them. I remember coming into the kitchen one night where there was a bucket of eels, with their heads cut off and they were moving!

There was a store in the village, but we had no pocket money to buy sweets. But there were not a lot of sweets that we could have bought, except butterballs and boiled lollies and licorice. I remember the first chocolate I ever ate. A girl who lived on a property out of the village had money and she bought chocolate and let us taste it. There were also very few commercially made biscuits. One thing I remember about my mother’s mother, grandma McInnis, who died on the first Anzac Day, was that she wouldn’t give me a biscuit.

All the games we played at school were English games. They had names like Oranges and Lemons, Jolly Miller, French and English, Sheep sheep come home, and a game like cricket called rounders. Many pupils came to school on horseback. I had a special friend called Grace and used to go to her place sometimes and try to ride horses. I fell off every time.

One day, Grace came with me to go across the creek to the Parsonage to get the milk. The Parsonage was a wonderful building with an attic. I never got to see the attic although my daughter did. It was a place of great mystery to me even to this day. When no one seemed to be at home, Grace and I, after we got the milk, decided we would go up the winding stairs and look in the attic. Grace went first, and as she was turning a corner in the stairs he tripped and spilled the milk. We were horrified and tried to mop up the milk with our pinafores. We then fled, and I never saw the attic.

My brother and I could read by the time we were 4. I was a keen scholar and read everything I could. We both loved books, especially books by Edward Ellis about a red Indian boy called Deerfoot. We also got Chatterbox and Little Folks and had quite a library. I was dying to go to school at five. I wanted to line up with the other children and march into school singing “Soldiers of the King”. When the tune was resurrected for the Breaker Morant film I was quite delighted.

The day came when I was able to go to school. I had a leather schoolbag and a collection of books and went off in high spirits. At 11 o’clock I came home again and said to my mother, “He won’t teach me o’s and a’s again”. When my mother asked me what happened, I said that he wouldn’t sharpen my pencil. I kept on scribbling away and expected my busy father to sharpen my pencil all the time. My father was a very good teacher and all the children he taught had a very good primary education and wrote with a good hand.

Hazel, Barry, & Gretel Ayre

Hazel, Barry, & Gretel AyreI am speaking about another world. In my childhood I couldn’t have dreamt of the comforts I have and the convenience I have in my old age. All the same, I would be glad if we did not have TV and fast cars that kill people. There are many more modern horrors besides atom bombs.

Living in the bush was always a struggle against ants and flies and mice. Once when we went away, mum had some Christmas puddings hanging by a string. She was confident that they would be safe from the ants but when we came home after some time, the ants had climbed down the string and eaten the middle out of the plum puddings. My husband Bill made a Coolgardie safe for me and Mum and for Nan and that was a blessing.

We had of course, no refrigeration, just the safe for meat. We got meat once or twice a week from Marulan and I still remember the lovely roast dinners we had on Sunday that seem to cook themselves while we were at church. That meant cold meat on Monday, a curry on Tuesday and perhaps soup made from the bones.

We had a vegetable garden and were given fruit and vegetables by friends and neighbours. Fruit in those days was untouched by fruit fly. We also caught rabbits which we soaked overnight in vinegar and water. They tasted like chicken. In those days chicken was a luxury meal usually had only at Christmas. We got eggs from our hens and when the hens were laying well, we preserved the eggs and kept them in a cool place in the pantry.

My mother was a wonderful cook, and spent a lot of time preparing food for people who would come into the village, a policeman, travelling salesman, the school inspector, ministers of religion. They would always be fed in the dining room with the white cloth and the best we had to offer. After she had provided the meal, Mum usually went to bed with a migraine. We entertained less important people like the woodman, swagman and more casual visitors in the kitchen.

Dad tried a few times to move from Bungonia. He and one of my sisters would sometimes go and inspect the new place, looking at the house, and we would get quite excited. We were even offered Norfolk Island. But Mum, a dreadful traveller, had one of her headaches and stayed in a dark room for three days. Mum didn’t like going out in public, so I often took her place. We never moved from Bungonia.

I remember the first motorcar in the village. The man at the hotel took us for a drive down the road. I was terrified. The trees rushed past us as we did at least 20 miles an hour. Sometimes we go in a T model Ford to Goulburn. The car had canvas sides and the windscreen wipers had to be moved by hand. It took at least three quarters of an hour to get to Goulburn.

Not even linoleum had been invented when I was a child. I remember the first lino we had and how excited everyone was when they were able to cover their bare boards with lino. Our floors were always scrubbed white but we had nice mats and were very comfortable.

Our lighting was kerosene lamps or candles. The toilet was a two seat pit toilet way down the back yard. At night time we would take a hurricane lamp or a candle. We often spend time there burning newspaper that we use as toilet paper and making patterns on the backs of our hands with candle wax. It’s a wonder we didn’t burn the place down!

Of course we had a fuel stove, but we had plenty of wood. When we needed the iron to iron Dad’s white shirts they had to be heated up on top of the stove, then wiped clean on a rag before Mum could begin to iron the shirt. One mistake and it had to be washed again. I remember when lounge suites came in. I had one of the first of them when I got married in 1932.

Other memories of my childhood are the birds including plagues of soldier birds. And kookaburras sitting on the clothesline and then suddenly making a dive into the hard

baked earth and finding a worm. How did they do it?

Our family roamed the bush, and I loved the bush. I had no worries or fears when I was in the bush. We went on long hikes. I remember camping down the Shoalhaven with Jack and some of his mates, camping on the sand.

Happiness is a childhood like mine.